Last week Joe McKendrick from ZDNet asked the question are SOA anti-principles more important than success principles? The idea of anti-principles came from Steve Jones, who a few years back did some nice work documenting SOA anti-patterns. In a post published last fall, Steve builds on his ideas, observing:

The problem is that there is another concept that is rarely listed, what are your anti-principles?

which is one of those good questions that should give you pause.

Steve continues:

In the same way as Anti-Patterns give you pointers when its all gone wrong then Anti-Principles are the things that you will actively aim to avoid during the programme.

I found this interesting because one of the anti-principles the post lists is direct calling. Steve describes this bad practice as follows:

This anti-principle is all about where people just get a WSDL and consume it directly without any proxy or intermediary. It’s programme suicide and it shouldn’t be done.

Naturally, because I’m in the business of building intermediaries, this seemed perfectly reasonable to me. But on reflection, I think that the argument as to why direct calling is an anti-principle needs further explanation.

Indirection is one of the great principles of computer science. Indirection lets us decouple layers, allowing these to change independently as long as they honour the interface contract. Intermediary layers in SOA, a good example being a proxy like Layer 7’s SecureSpan Gateway, build on this concept allowing architects to decouple service providers from consumers—much as Steve advocates in his post. This layer of indirection means that we can tease out certain highly parameterizable aspects of communication—aspects such as security, monitoring, protocol adaptation, routing, etc.—into a separate policy layer that promotes consistency, affords the opportunity for reuse, and insulates clients (and servers) from change.

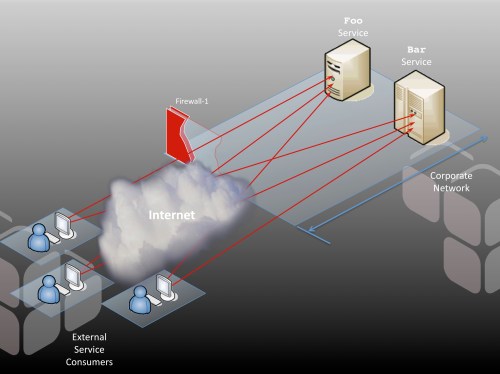

This is best illustrated by example. Suppose I have two services: foo and bar. Both services have a number of clients that access them. To explore the issues with direct connection, let’s consider the scenario where all of these clients establish direct connections with my services:

The first thing you should notice is that the firewall is open to allow the external clients to make their direct connections with the service hosts. In other words, these hosts are, for all intents and purposes, deployed in the DMZ and must be hardened under that assumption. For many applications, this is a non-trivial exercise. Hopefully, your internal alarm bells are going off already.

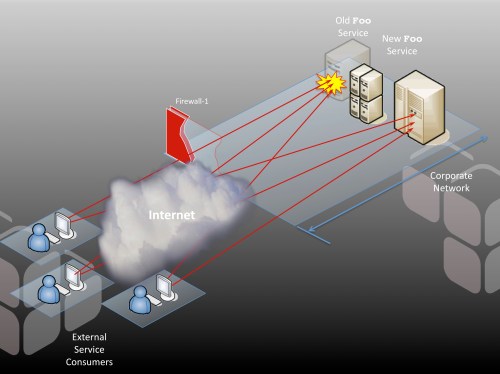

Few applications remain completely static over their lifetime. Patches become necessary; hardware fails and must be replaced—all of this is part of the natural life cycle of software. My services foo and bar are no exception. One day, the server hosting foo starts to fail, and I find myself in the position that I need to quickly move the foo service onto a new host. Suddenly, all of my clients are broken:

Now I have a very significant problem. I need to update the URLs on every client I serve, and to do it quickly. Every minute I’m down, I’m losing business. Welcome to the pressure cooker.

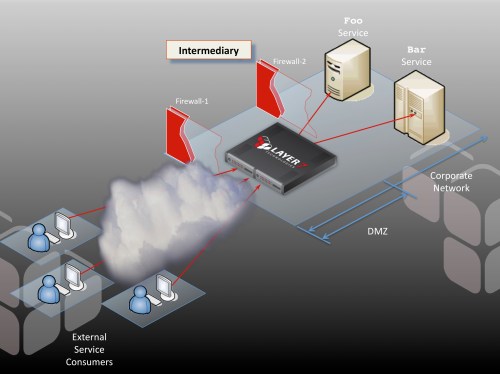

This potential problem would be easy to manage if I had an intermediary, operating as a policy-driven proxy that is placed in the DMZ between my clients and my services:

This proxy now handles URL-based routing on the fly. If foo moves, it’s a simple matter of modifying the internal routing on the intermediary and voila: no client ever has a problem. My client base is completely insulated from a major structural change to my back end service hosts.

Of course there are tricks we could use employing HTTP redirects, common NAT, or more dynamic bindings to URLs to avoid such a contrived problem in the first place. But what if the change was to something less configurable using conventional means, such as the basic security model for communication? Suppose that as a corporation, we decide to mandate that all clients must now authenticate using client-side certificates under SSL? Foo is running on a Java application server, bar is on .NET; both are capable of accommodating this new model, but their administration is radically different. And to make matters worse, I have a dozen or so additional apps implemented in everything from Ruby on Rails to PHP that I also need to change. That’s a lot of work.

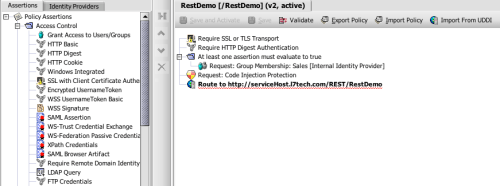

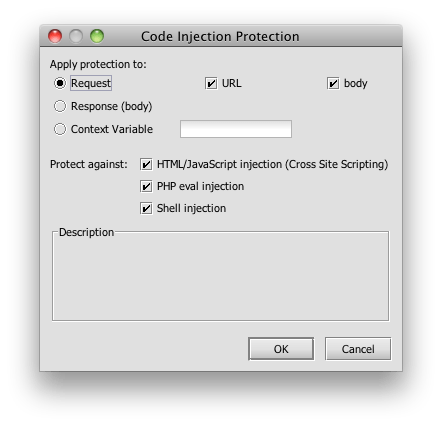

An intermediary would make this task trivial by insulating services from this change to policy. The strategy here is to terminate the SSL connection and authenticate the client on the intermediary instead of on the service hosts. A few clicks of a mouse later, and my job is complete for every service.

This certainly saves time and adds consistency, but the real value is in the change of responsibility. The task of implementing this security model now falls under the jurisdiction of a professional security administrator, not the developers of each separate application. In fact, no code or configuration needs to change on foo, bar, or any of my services. The security model is decoupled from the application, taken out of the hands of each developer and centralized. This is the basic value proposition of intermediaries in SOA, and this value is never realized effectively if you allow direct connections between clients and servers. This is why architectural patterns are sometimes necessary to allow us to be consistent with our principles—or our anti-principles, as the case may be.

Interested in trying an intermediary? You can get a Layer 7 SecureSpan virtual appliance to try out at http://www.layer7tech.com. Alternatively, do your evaluation completely in the cloud. Check out the SecureSpan virtual appliance gateway on the Amazon marketplace. This virtual appliance AMI runs in the EC2 cloud on Amazon Web services. It is the first and only SOA gateway to run in the cloud.

This morning, I recorded a podcast with Keith Shaw from Network World. Our discussion was about the 5 mistakes people make when moving out into the cloud. The podcast should be available next week, but in the meantime, I thought I would share a nice analogy that Keith came up with illustrating the difference between public and private clouds.

This morning, I recorded a podcast with Keith Shaw from Network World. Our discussion was about the 5 mistakes people make when moving out into the cloud. The podcast should be available next week, but in the meantime, I thought I would share a nice analogy that Keith came up with illustrating the difference between public and private clouds.