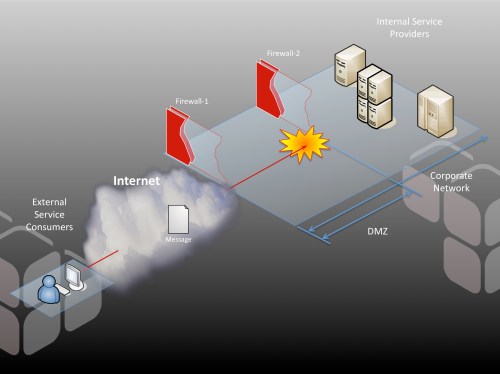

So you’ve bought into the idea of service-orientation. Congratulations. You’ve begun to create services throughout your internal corporate network. Some of these run on .NET servers; others are Java services; still others are Ruby-on-Rails—in fact, one day you woke up and discovered you even have a mainframe service to manage. But the question you face now is this: how can all of these services be made available to consumers on the Internet? And more important, how can you do it securely?

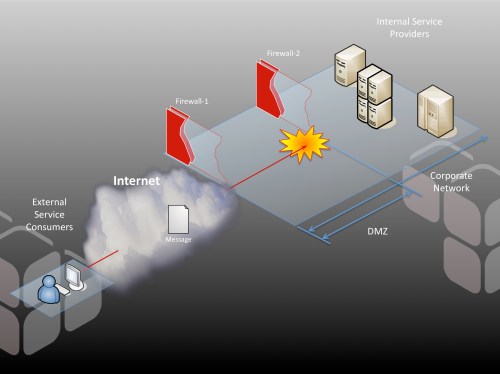

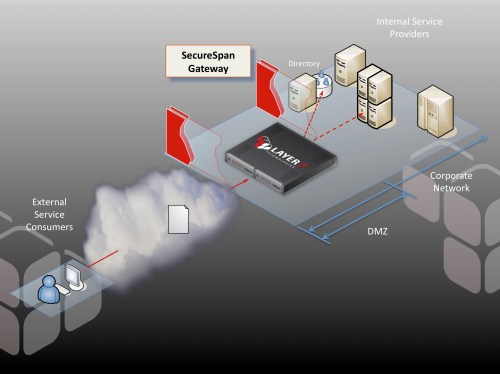

Most organizations buffer their contact with the outside world using a DMZ. Externally facing systems, such as web servers, live in the DMZ. They mediate access to internal resources, implementing—well, hopefully implementing—a restrictive security model. The DMZ exists to create a security air gap between protocols. The idea is that any system deployed into the DMZ is hardened, resilient, and publishes a highly constrained API (in most cases, a web form). To access internal resources, you have to go through this DMZ-based system, and this system provides a restricted view of the back-end applications and data that it fronts.

The DMZ represents a challenge for publishing services. If services reside on internal systems, how can external clients get through the DMZ and access the service?

Clearly, you can’t simply start poking holes in firewall #2 to allow external systems to access your internal providers directly; this would defeat the entire purpose of the DMZ security model. But this is exactly what some vendors advocate. They propose that you implement local security agents that integrate into the container of the internal service provider. These agents implement policy-based security—essentially taking on the processing burden of authentication, authorization, audit, confidentiality, integrity and key management. While this may seem attractive, as it does decouple security into a purpose-built policy layer, it has some very significant drawbacks. The agent model essentially argues that once the internal policy layer is in place, the internal service provider is ready for external publication. But this implies poking holes in the DMZ, which is a bad security practice. We have firewalls precicely because we don’t want to harden every internal system to DMZ-class resiliancy. An application-layer policy agent does nothing to defeat OS-targetted attacks, which means every service provider would need to be sufficiently locked down and maintained. This becomes unmanagable as the server volume grows, and completely erodes the integrity of firewall #2.

Furthermore, in practice, agents just don’t scale well. Distribution of policy among a large number of distributed agents is a difficult problem to solve. Policies rapidly become unsynchronized, and internal security practices are often compromised just to get this ponderous and dependent system to work.

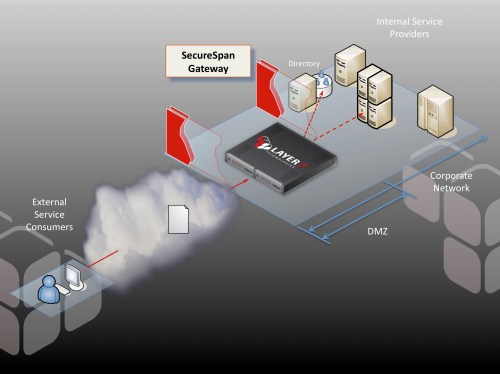

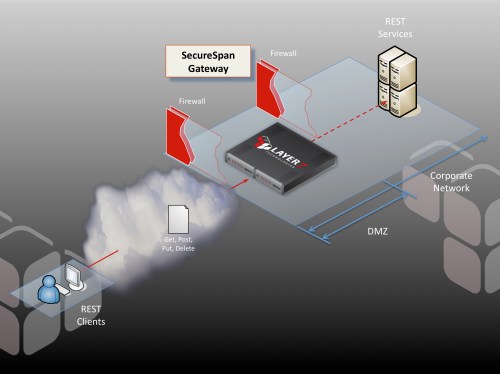

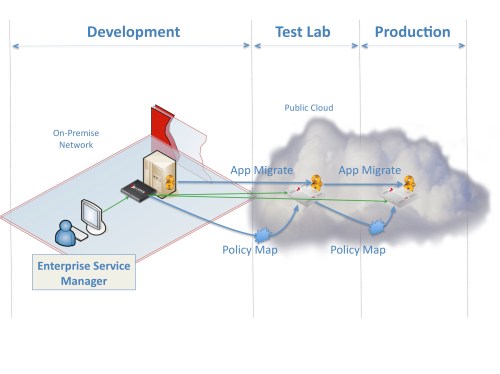

At Layer 7 we advocate a different approach to publishing services that is both scalable and secure. Our flagship product, the SecureSpan Gateway, is a security proxy for Web services, REST, and arbitrary XML and binary transactions. It is a hardened hardware or virtual appliance that can be safely deployed in the DMZ to govern all access to internal services. It acts as the border guard, ensuring that each transaction going in or out of the internal network conforms to corporate policy.

SecureSpan Gateways act as a policy air-gap that constrains access to back end services through a rich policy-based security model. This integrates consistently with the design philosophy of the DMZ. Appliances are hardened so they can withstand Internet-launched attacks, and optimized so they can scale to enormous traffic loads. We built full clustering into SecureSpan in the first version we released, close to eight years ago. This ensures that there is no single point of failure, and that systems can be added to accommodate increasing loads.

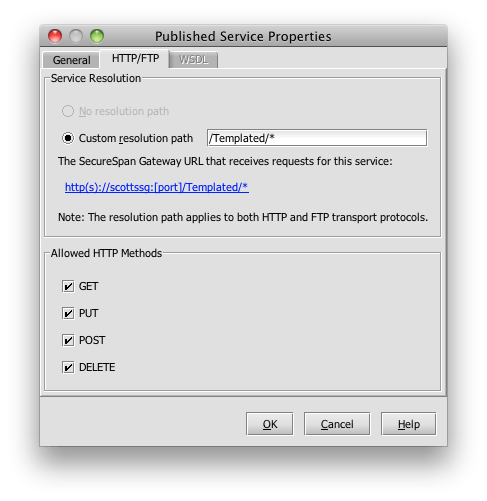

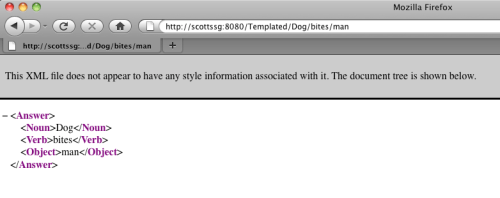

The separate policy layer—and the policy language that defines this—is the key to the security model and is best illustrated using a real example. Suppose I have a warehouse service in my internal network that I would like to make available to my distributors. The warehouse service has a number of simple operations, such as inventory queries and the ability to place an order. I’ll publish this to the outside world through a SecureSpan Gateway residing in the DMZ, exactly as shown in the diagram above.

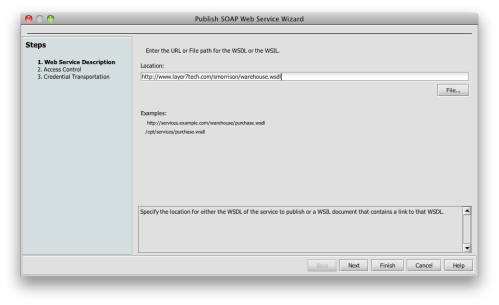

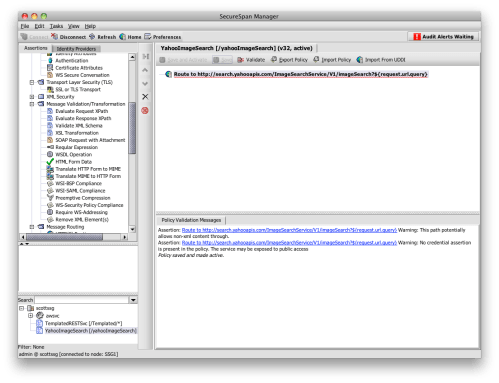

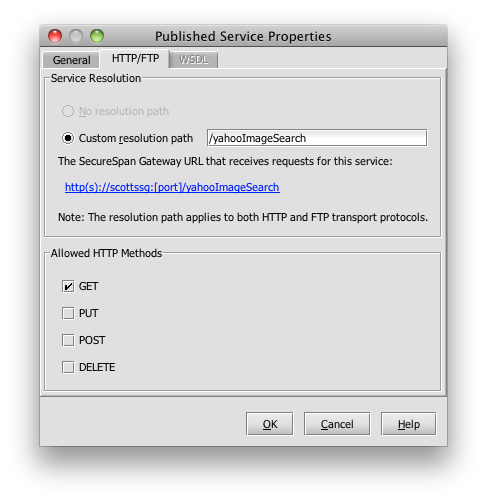

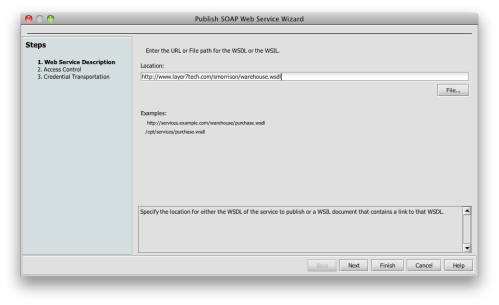

SecureSpan provides a management console used to build the policies that govern access to each service. Construction of the initial policy is made simple using a wizard that bootstraps the process using the WSDL, which is a formal service description for my warehouse service. The wizards allows me to create a basic policy in three simple steps. First, I load the WSDL:

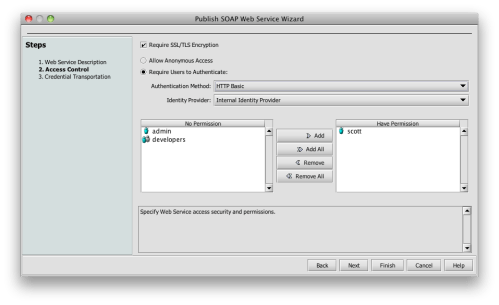

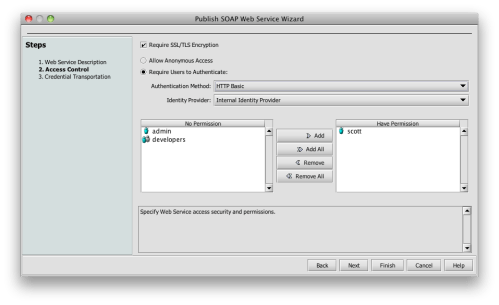

Next, I declare a basic security model. I’ll keep this simple, and just use SSL for confidentiality, integrity, and server authentication. HTTP basic authentication will carry the credentials, and I’ll only authorize access to myself:

Next, I declare a basic security model. I’ll keep this simple, and just use SSL for confidentiality, integrity, and server authentication. HTTP basic authentication will carry the credentials, and I’ll only authorize access to myself:

If this policy sounds familiar, it’s because it’s the security model for most web sites. It turns out that this is a reasonable model for many XML-based Web services as well.

If this policy sounds familiar, it’s because it’s the security model for most web sites. It turns out that this is a reasonable model for many XML-based Web services as well.

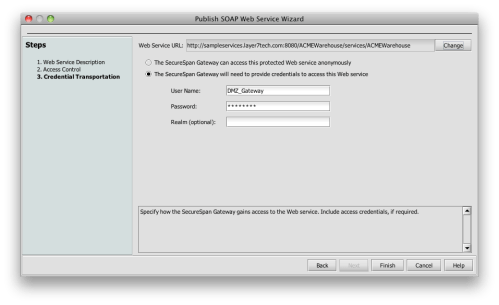

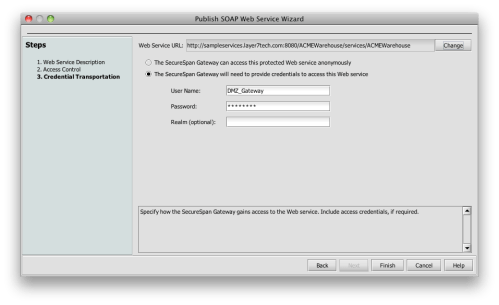

Finally, I’ll define a proxy routing to get to my internal service, and an access control model once there. In this example, I will just use a general account. Under this model, the service trusts the SecureSpan Gateway to authenticate and authorize users on it’s behalf:

You may have noticed that this assumes that the warehouse services doesn’t need to know the identity of the original requester-—that is, Scott. If the service did need this, there are a number of ways to communicate my identity claim downstream to the service, using techniques like SAML, IBM’s Trust Association Interceptor (TAI), proxied credentials, or various other tricks that I won’t cover here.

You may have noticed that this assumes that the warehouse services doesn’t need to know the identity of the original requester-—that is, Scott. If the service did need this, there are a number of ways to communicate my identity claim downstream to the service, using techniques like SAML, IBM’s Trust Association Interceptor (TAI), proxied credentials, or various other tricks that I won’t cover here.

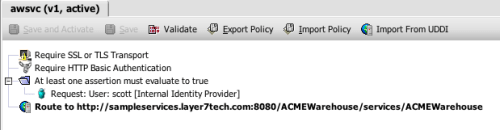

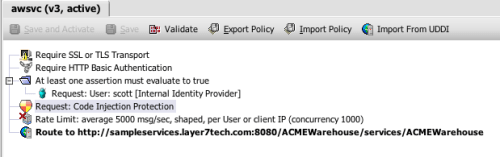

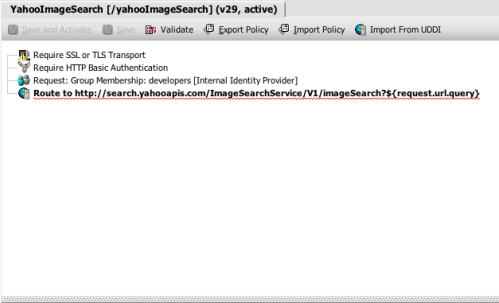

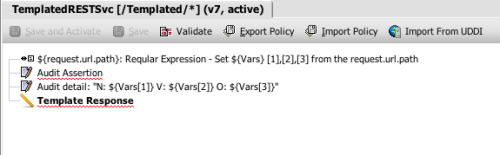

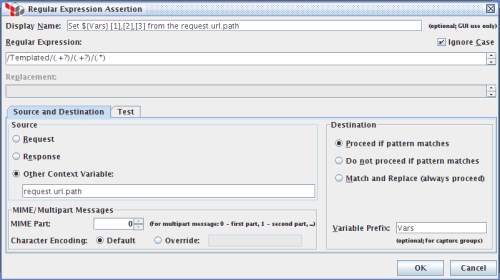

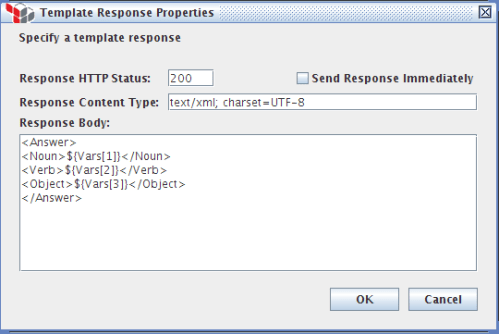

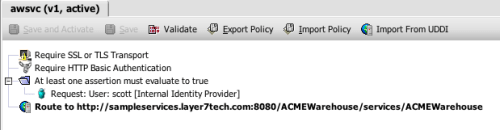

The wizard generates a simple policy for me that articulates my simple, web-oriented security model. Here’s what this policy looks like in the SecureSpan management console:

Policy is made up of individual assertions. These encapsulate all of the parameters that make up that operation. When a message for the warehouse service is identified, SecureSpan loads and executes the assertions in this policy, from top to bottom. Essentially, policy is an algorithm, with all of the classic elements of flow control. SecureSpan represents this graphically to make the policy simple to compose and understand. However, policy can also be rendered as an XML-based WS-Policy document. In fact, if you copy a block of graphical assertions into a text editor, they resolve as XML. Similarily, you can paste XML snippets into the policy composer and they appear as graphical assertion elements.

Policy is made up of individual assertions. These encapsulate all of the parameters that make up that operation. When a message for the warehouse service is identified, SecureSpan loads and executes the assertions in this policy, from top to bottom. Essentially, policy is an algorithm, with all of the classic elements of flow control. SecureSpan represents this graphically to make the policy simple to compose and understand. However, policy can also be rendered as an XML-based WS-Policy document. In fact, if you copy a block of graphical assertions into a text editor, they resolve as XML. Similarily, you can paste XML snippets into the policy composer and they appear as graphical assertion elements.

This policy is pretty simplistic, but it’s a good foundation to build on. I’ll add some elements that further restrict transactions and thus constrain access to the back end system the SecureSpan Gateway is protecting.

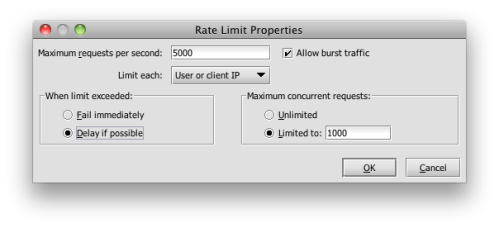

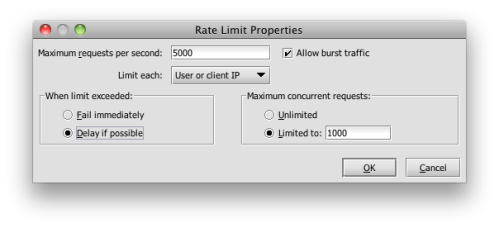

The rate limit assertion allows me to cap the number of transactions getting through to the back end. I can put an absolute quota on the throughput: say, 30,000 transaction/sec because I know that the warehouse service begins to fail once traffic exceeds this volume. But suppose I was having a problem with individual suppliers overusing particular services. I could limit use by an individual identity (as defined by an authenticated user or originating IP address) to 5,000 transasctions/sec—still a lot, but leaving headroom for other trading partners. The rate limit assertion gives me this flexibility. Here is its detailed view:

Note that if I get 5,001 transactions from a user in one second, I will buffer the last transaction until the rate drops in a subsequent time window (subject, of course, to resource availability on the gateway). This provides me with application-layer traffic shaping that is essential in industries like telco, who use this assertion extensively.

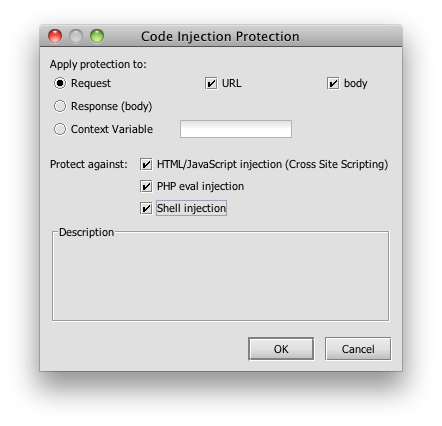

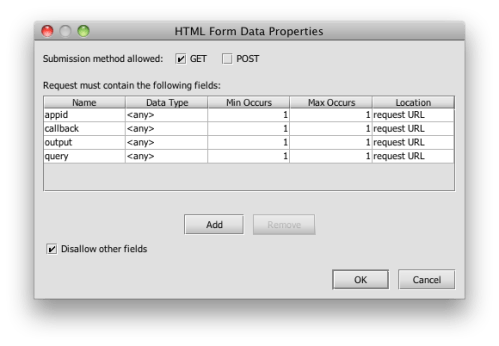

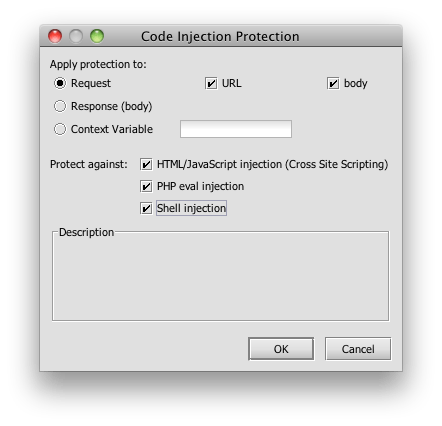

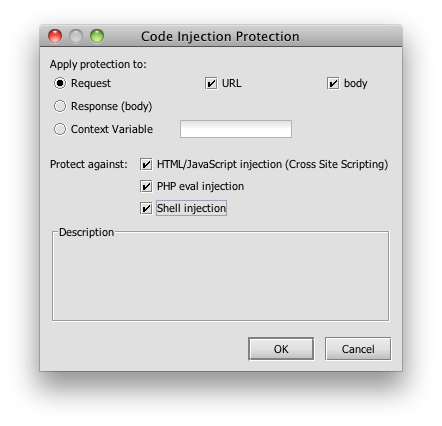

I would also like to evaluate each new transaction for threats. SecureSpan has assertions that cover a range of familar threats, such as SQL-injection (which has been around for a long time, but has become newly relevant in the SOA world), as well as a long list of new XML attacks that attempt to exploit parser infrastructure and autogenerated code. For the warehouse service, I’m concerned about code-injection attacks. Fortunately, there’s an assertion for that:

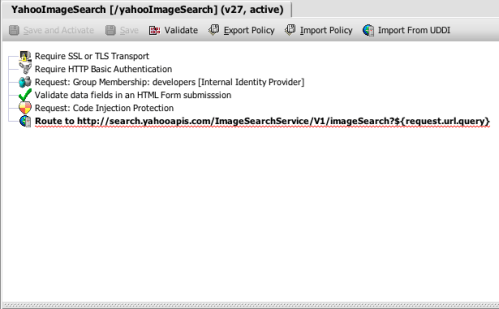

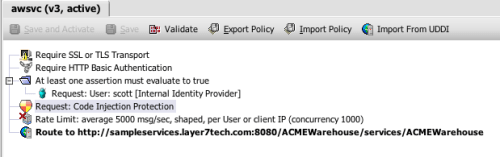

Here’s what these two assertions look like dropped into the policy:

This policy was simple to compose (especially since we had the wizard to help us). But it is also very effective. It’s a visible and understandable, which is an important and often overlooked aspect of security tooling. SOA security suffers from an almost byzantine complexity. It is much too easy to build a security model that obscures weakness behind its detail. One of the design goals we had at Layer 7 for SecureSpan was to make it easy to do the simple things that challenge us 80% of the time. However, we also wanted to provide the richness to solve the difficult problems that make up the other 20%. These are problems such as adaptation. They are the obscure impedance-mismatches between client and server security models, or fast run-time adaptation of message content to accommodate version mismatches.

In this example, it took only seven simple assertions to build a basic security policy for publishing services to the outside world. Fortunately, there are over 100 other assertions—covering everything from message-based security to transports like FTP to orchestration—that are there when you need to solve the tougher problems.