One emerging technology that has recently caught our attention here at Layer 7 is the Open Data Protocol, or OData for short. You can think of OData as JDBC/ODBC for the web. Using OData, web developers can query data sources in much the same way they would use SQL. It builds on the basic CRUD constructs of REST, adding the Atom Publishing Protocol to help flesh out the vision under a very standards-oriented approach. OData’s major promoter is Microsoft, but the company is clearly intent on making this protocol an important community-driven initiative that provides value to all platforms.

I like OData; but as with any power tool, I approach it with care and some suspicion. I definitely agree that we need a formalized approach to interacting with Web data sources. OData is not SQL, but it brings enough familiar constructs with it to make the protocol easy to pick up and tremendously versatile. But OData also raises some significant security issues that need to be carefully considered before it is deployed.

Most applications are designed to constrain a user’s view of data. Any modern relational database has the ability to apply access control and limit a user’s view to the records to which they are entitled. More often than not, however, the enforcement of these entitlements is a task delegated not to the database, but to the application that interacts with it.

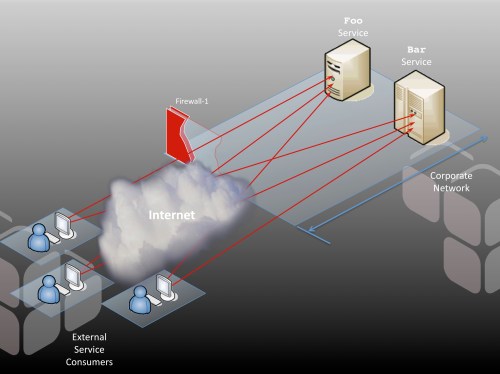

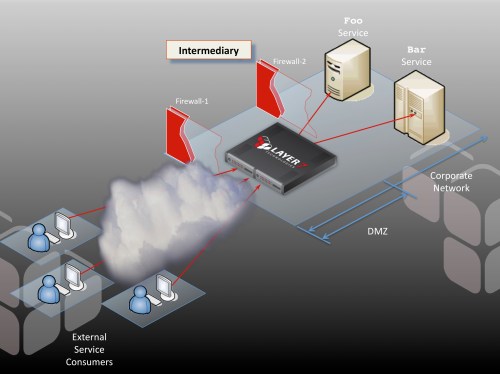

Consider, for example, a scenario, where a database makes a JDBC or ODBC connection directly available to clients outside of the corporate firewall:

It can be extremely risky to permit direct outside connections into a database.

People avoid doing this for a good reason. It is true that you can secure the connection with SSL and force the incoming user to authenticate. However, if an attacker was able to compromise this connection (perhaps by stealing a password), they could explore or alter the database at will. This is a gangster’s paradise.

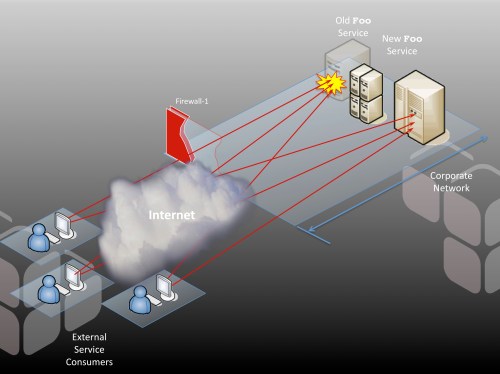

A simple web application is really a security buffer zone between the outside world and the database. It restricts the capabilities of the user through the constraints imposed by elements that make up each input form. Ultimately, the application tier maps user interactions to explicit SQL statements, but a well-designed system must strictly validate any incoming parameters before populating any SQL templates. From this perspective, web applications are fundamentally a highly managed buffer between the outside world and the data—a buffer that has the capability of applying a much more customizable and rigorous model of access control than a RDMS could.

The Web application tier as security buffer between the database and the Internet.

However, this is also why SQL injection can be such an effective vector of attack. An application that fails to take the necessary precautions to validate incoming data can, in effect, extend the SQL connection right outside to the user. And unconstrained SQL can open up the entire database to examination or alteration. This attack vector was very popular back in the PowerBuilder days, but lately it has made a startling resurgence because its effectiveness when applied to badly designed web apps.

OData, of course, is the data source connection, so injection isn’t an issue—just getting a hold of it in the first place is enough. So what is critically important with OData is to strictly manage what this connection is capable of doing. OData servers need to provide not just authentication, authorization, and audit of the connection, but wholesale constraint of protocol function and data views as well. Web security demands that you assume the worst—and in this case, the worst is certainly compromise of the connection. The best way to manage this risk is to limit your exposure to what an attacker can do.

In SQL-terms, this is like limiting the functions that a user can access, and restricting them to the views to which they are entitled (and they shouldn’t be entitled to much). The danger with OData is that some of the tools make it much too easy to simply open a connection to the data (“click here to make the database available using OData”); this can have widespread negative consequences if an attacker is able to compromise a legitimate user’s account. If the data source cannot itself impose the necessary constraints on the connection, then an intermediate security layer is mandatory.

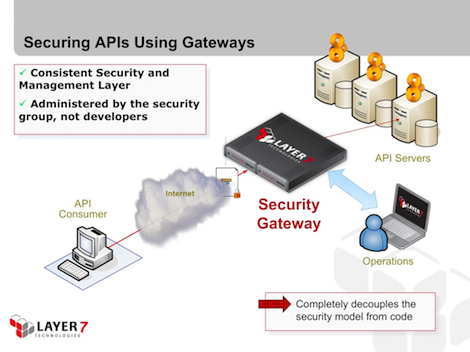

This is where Layer 7 can help. CloudSpan is fully compatible with OData, and can act as an independent security layer between the OData client (which may be a browser-resident application) and the OData server. It can offer not just AAA on the connection, but can narrow the OData API or mask query results based on an individual user’s entitlement.

CloudSpan Gateways managing access to OData data sources.

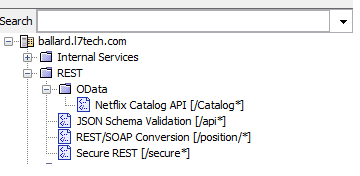

Here’s a real example that Julian Phillips, one of Layer 7’s architects, put together. Jules constructed a policy using the Netflix OData API, which is an experimental service the company has made available on the net. The Netflix API allows you to browse selections in their catalog. It has it’s own constraints built in—it’s already read-only, for example—but we are going to show how CloudSpan could be deployed to further constrain the API to implement stricter security protocols, and even enforce business rules governing access.

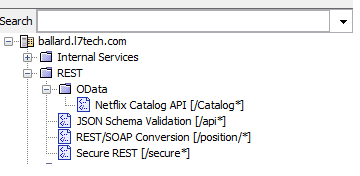

Jules’ policy is activated on all URI’s that match the /Catalog* patternthe entry point into the Netflix OData API. This shows up in CloudSpan under the service browser:

What we are going to do here is add some security constraints, and then a business rule that restricts the ability of minors to only view movie titles with a rating of G or PG-13. Minors can build perfectly valid Netflix OData queries and submit them to the API; however, these will be trapped by the CloudSpan gateway before they get to the actual OData server.

Jules’ basic policy is quite simple. We’ve collapsed some details into folders to make the basic flow easier to understand:

First off, the policy throws an explicit audit to capture both the URI and the query string for debugging purposes. We then ensure that the connection uses SSL (and subject to the cipher suite constraints currently in effect), and we mine HTTP basic credentials from the connection. Need Kerberos or SSL client-side certificate authentication instead? Just drag the assertions implementing either of these into the policy and you are good to go.

The gateway then authenticates the user against a directory, and from this interaction we determine whether this user is an adult or a minor based on their group membership. If the user is indeed an adult, the gateway passes their OData query to the server unchanged. However, if the user is a minor, the gateway adds constraints to the query to ensure that the server will only return G or PG-13 movies. For reference, the full policy is below (click to expand):

This example is somewhat contrived, but you should be able to see how the intermediate security gateway can add critical constraint to the scope of OData protocol. OData shows a lot of promise. But like many new technologies, it needs to be managed with care. If deployed securely, OData can become an essential tool in any web developer’s toolkit.