On the eve of the RSA conference this year, Chris Comerford and Pete Soderling published a provocative article in Computerworld titled Why REST security doesn’t exist. It’s a prelude to a talk the author’s are delivering at the conference. Their premise is that while good REST security best practices do indeed exist, developers just don’t seem to follow them.

Comerford and Sodering attribute this state of affairs to a combination of two things. First, REST lacks a well-articulated security model. Few would argue with this—REST, by virtue of its grassroots origins, suffers from a security just-do-it-like-the-web nonchalance that’s certainly done it no favors.

The second issue concerns developers who tend to rush implementation without giving due consideration to security. Truthfully, this is the story of security across all of IT, but I might suggest that with REST, the problem is especially acute. The REST style owes much of its popularity to being simple and fast to implement, particularly when faced with the interest-crushing complexity and tooling demands of the WS-* stack. It’s reasonable to think that in the enthusiastic dash to cross the working application finish line, that security is conveniently de-emphasized or forgotten altogether.

REST, of course, can be secured, and the author’s offer sound advice to accomplish this deceptively simple task. They recommend that API developers:

- “Do employ the same security mechanisms for your APIs as any web application your organization deploys. For example, if you are filtering for XSS on the web front-end, you must do it for your APIs, preferably with the same tools.

- Don’t roll your own security. Use a framework or existing library that has been peer-reviewed and tested. Developers not familiar with designing secure systems often produce flawed security implementations when they try to do it themselves, and they leave their APIs vulnerable to attack.

- Unless your API is a free, read-only public API, don’t use single key-based authentication. It’s not enough. Add a password requirement.

- Don’t pass unencrypted static keys. If you’re using HTTP Basic and sending it across the wire, encrypt it.

- Ideally, use hash-based message authentication code (HMAC) because it’s the most secure. (Use SHA-2 and up, avoid SHA & MD5 because of vulnerabilities.) “

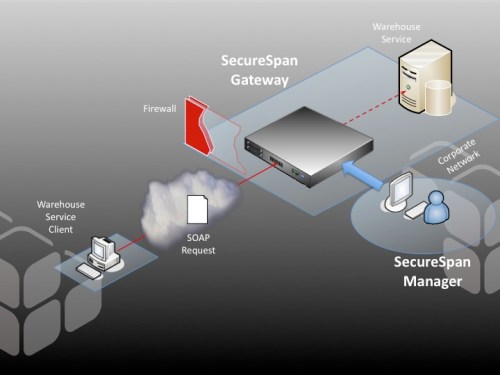

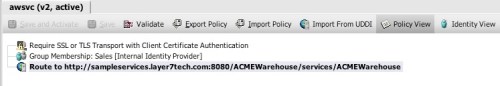

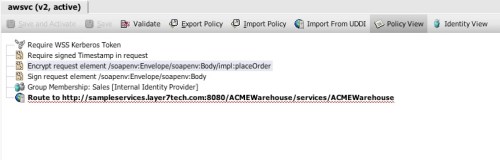

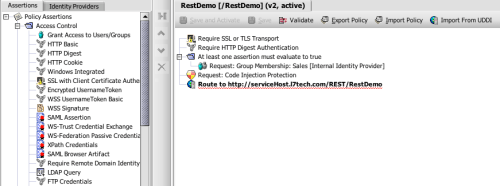

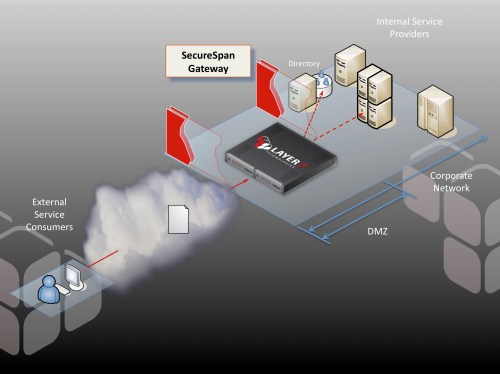

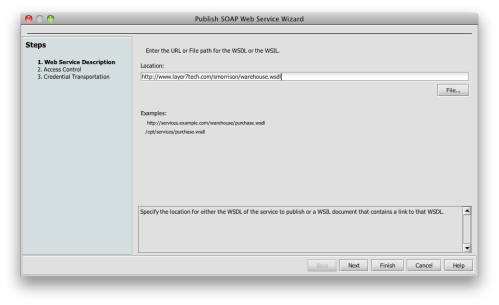

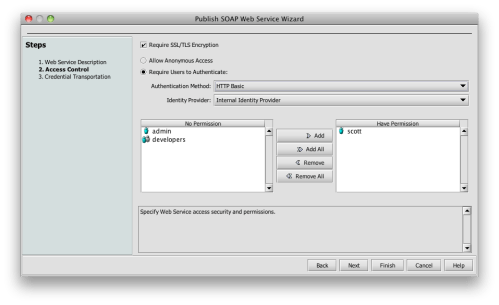

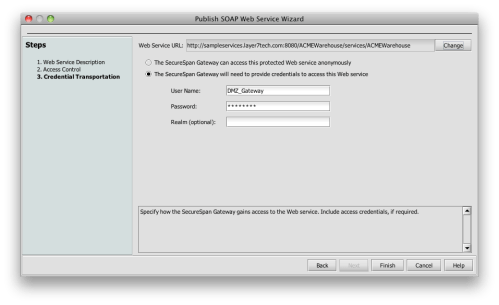

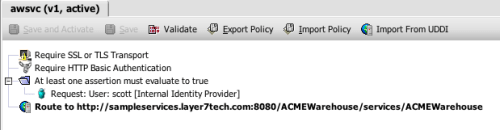

I agree with this advice. And just to demonstrate how easy it is to implement, I’ve constructed a simple policy for the Layer 7 Technologies SecureSpan Gateway demonstrating their directives:

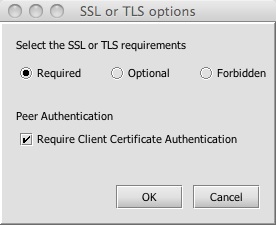

In this policy, I’m ensuring that the REST client is using SSL for three things: confidentiality, integrity, and server authentication. I could require client-side certificate authentication here, but instead I’m using HTTP digest, to emphasize the requirement to avoid using plain text HTTP basic or simple user keys. I’m authorizing access based on group membership here, restricting access to members of the sales group.

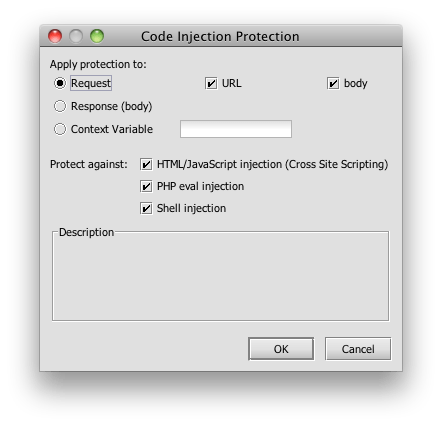

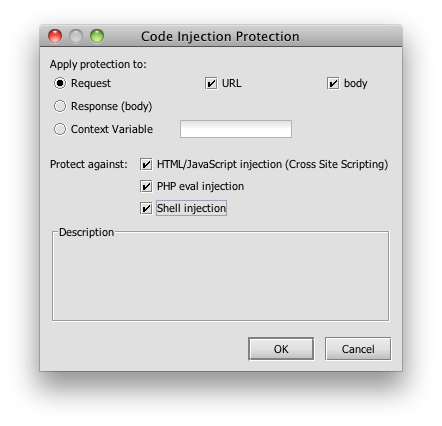

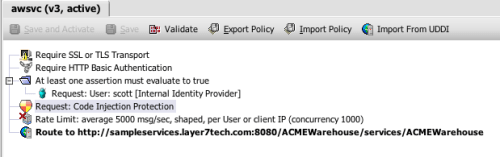

Finally, I’ve added a scan for cross site scripting attacks.

In the interest of deeper vigilance, I’m also searching for PHP and shell injection signatures. This is admittedly broad, but it covers me in case the developer of the service changes implementation without warning.

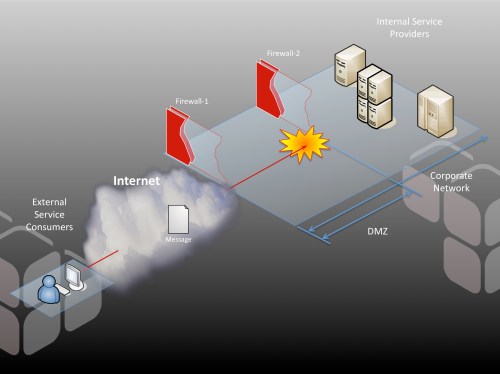

This last point—that there is an explicit separation made between developers and the security administrators writing and enforcing policy—is an important one. Developers will be developers: some will be rigorous about implementing security best practices; others won’t be. The only way to manage this is to assume a defensive posture in service policy, both from the perspective of incoming transactions, but also around the services themselves. The best practice here is to externalize policy enforcement and assign dedicated security professionals to administer policy.

This defensive approach to securing REST services fits well with the spirit of Comerford and Soderling’s directives. It addresses, in particular, their point about leveraging peer-reviewed frameworks. This is precisely what Layer 7’s SecureSpan Gateway is—a peer-reviewed security framework offering great depth of functionality. SecureSpan is undergoing Common Criteria Review of its implementation, as well as the entire development process for the product. We’re certifying to EAL4+, which is particularly rigorous. This provides assurance that the technology is sufficiently robust for deployment at the highest levels of military and the government. Common Criteria is an arduous process, and going through it demonstrates Layer 7’s deep commitment to security. You should not ever consider a security gateway—for REST, or for XML messaging—that isn’t undergoing the Common Criteria evaluation. Remember, Common Criteria is a necessary stamp of approval for governments around the world; it should also be a basic requirement for you.

Try SecureSpan yourself, and see how you can implement robust application security and monitoring without changing code. Download an evaluation of the SecureSpan virtual appliance right here.

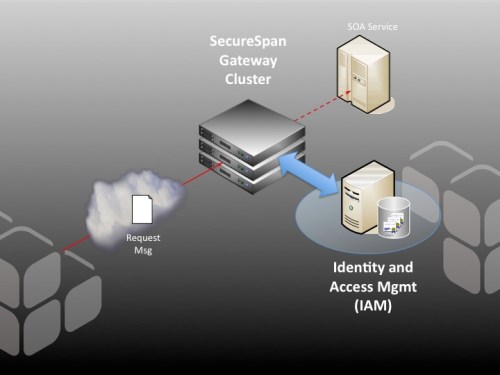

an investment in Identity and Access Management (IAM) infrastructure; however, this is not sufficient on its own for SOA access control. That’s where Layer 7 can help. Deployed in combination with an IAM system like OpenSSO, SecureSpan does the heavy lifting of XML processing and enforcement, but delegates the access control decision process (and often identity token validation) to the existing, familiar IAM infrastructure. It’s a powerful combination, and one that extends existing investment in IAM into the SOA world.

an investment in Identity and Access Management (IAM) infrastructure; however, this is not sufficient on its own for SOA access control. That’s where Layer 7 can help. Deployed in combination with an IAM system like OpenSSO, SecureSpan does the heavy lifting of XML processing and enforcement, but delegates the access control decision process (and often identity token validation) to the existing, familiar IAM infrastructure. It’s a powerful combination, and one that extends existing investment in IAM into the SOA world.